After reading Homer’s Iliad, I’m continuing with the theme of great war novels. I recently read Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front.

Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine motivated me to finally read War and Peace (translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, 2007; Vintage Classics edition, 2008), but I never expected in taking up this novel that I would run across a connection to my family history. Footnote 14, Volume II, Part 3 (p. 1234) reads: “the Finnish war: At the instigation of Napoleon, who wanted to punish Sweden for its alliance with England, Alexander I began a war with Sweden in February 1808, which ended with the Russian annexation of Finland.”

Quoting from a letter written April 20, 1921, from my great-great grand mother, Amalia, to her daughter, there is additional information about the family background of Amalia’s maternal ancestry:

“My grandmother on my mother’s side came from Finland when she was 16 years old, when she and a girl companion ran away from Finland when the war of 1809 broke out between Russia and Finland. Finland went under Russia’s rule in 1809. Sweden lost her rule over Finland then. She had evidently made up her mind that she would not be a subject of Russia, and I have heard that those two girls walked all the way to Stockholm. I have a sort of remembrance that it was in the wintertime, but am not sure.”

~ ~ ~

Here are some other things that I learned from reading War and Peace.

Regarding war in general:

Vladimir Putin justifies his invasion of Ukraine partly on “Russian culture.” He should remember the words of Leo Tolstoy: “On the twelfth of June, the forces of Western Europe crossed the borders of Russia, and war began—that is, an event took place contrary to human reason and to the whole of human nature. Millions of people committed against each other such a countless number of villainies, deceptions, betrayals, thefts,…arsons, and murders as the annals of all the courts in the world could not assemble in whole centuries, and which, at that period of time, the people who committed them did not look upon as crimes.” (Vol. I, p. 603).

Contemplating the possible causes of that war, Tolstoy includes: “Napoleon’s love of power,” “autocratic power in Russia,” and “if all the sergeants had been unwilling to enlist for a second tour of duty, there also could have been no war.” (Vol. 3, Part 1, Chapter 1.)

I based my conscientious objector claim during the Vietnam War partly on that last piece of logic—in the parlance of the late 1960s, “What if they gave a war and no one came?”

~ ~ ~

Regarding Napoleon, Putin, and Trump:

Napoléon in his coronation robes by François Gérard, c. 1805. –from Wikipedia.

Photo by YURI KADOBNOV/AFP via Getty Images; photoshopped by Ken Barker

“It was obvious that Balashov’s person did not interest him in the least. It was clear that only what went on in his soul was of interest to him. Everything that was outside him had no meaning for him, because everything in the world, as it seemed to him, depended only upon his will.”

Vol. I, p. 619

“Not only was there no expression in him of embarrassment or self-reproach for his morning’s outburst, but, on the contrary, he tried to encourage Balashov. Clearly it was Napoleon’s long-standing conviction that the possibility of mistakes did not exist for him, and to his mind everything he did was good, not because it agreed with any notion of what was good and bad, but because he did it.”

Vol. I, p. 624

“And again he was transferred to his former artificial world of phantoms of some sort of greatness, and again…he began to obediently fulfill that cruel, sad, oppressive, and inhuman role which had been assigned to him.

“And not only for that hour and day were reason and conscience darkened in this man who, more than all the other participants in this affair, bore upon himself the whole weight of what was happening; but never to the end of his life was he able to understand goodness, or beauty, or truth, or the meaning of his own actions, which were too much the opposite of goodness and truth, and too far removed from everything human for him to be able to grasp their meaning. He could not renounce his actions, extolled by half the world, and therefore he had to renounce truth and goodness and everything human.”

Vol. II, p. 815

~ ~ ~

Regarding today’s Ukrainian fighters:

“By many years of military experience he [General Kutuzov] knew, and by his old man’s mind he understood, that one man cannot lead hundreds of thousands of men struggling with death, and he knew that the fate of a battle is decided not by the commander in chief’s instructions, not by the position of the troops, not by the number of cannon or of people killed, but by that elusive force known as the spirit of the troops, and he watched this force and guided it, as far as that lay in his power.”

Vol. II, p. 805

“One of the most palpable and advantageous deviations from the so-called rules of war is the action of scattered people against people pressed together in a mass. This kind of action always emerges in a war that acquires a national character. These actions consist in the fact that, instead of a crowd opposing a crowd, people scatter, attack singly, and flee as soon as large forces attack them, then attack again as soon as the opportunity arises. This was done by the guerrillas in Spain; it was done by the mountaineers in the Caucasus; it was done by the Russians in the year 1812.

“Warfare of this kind has been named partisan warfare, and those who named it supposed that by doing so they were explaining its meaning. Yet this kind of warfare not only does not fit into any rules, but is directly opposed to a tactical rule that is well-known and acknowledged as infallible. This rule says that an attacker should concentrate his troops in order to be stronger at the moment of battle.

“Partisan warfare (always successful, as history demonstrates) is directly opposed to this rule.”

Vol. IV, p. 1033

It goes without saying that the winning side in the American Revolution and in the Vietnam War used this strategy.

~ ~ ~

Regarding Christian hypocrisy:

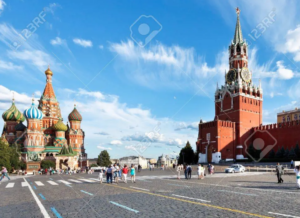

Image 1) Red Square, Saint Basil cathedral and the Kremlin wall in Moscow; Image 2) big barrel of Tsar Cannon and Dormition cathedral in Moscow Kremlin.

“We all confess the Christian law of forgiveness of offenses and love of one’s neighbor, a law in consequence of which we have erected forty times forty churches in Moscow—but yesterday a deserter was flogged to death, and a priest, a servant of that same law of love and forgiveness, gave him the cross to kiss before the execution.” So Pierre reflected, and accustomed as he was to it, this whole general, universally acknowledged lie amazed him each time like something new. “I understand this lie and confusion,” he thought, “but how can I tell them all that I understand it? I’ve tried, and I’ve always found that in the depths of their souls, they understand the same thing I do, but they simply try not to see it.”

Vol II, p. 537

All the violence during this year’s Holy Week shows how religions have failed the human race, or the human race has failed religion.

Similarly in Medicine For The Blues Dr. Carl Holman returns from WWI disillusioned with religion and mankind and deploring humanity’s willful blindness.

Putin must have read War and Peace in his Russian education. Did he learn anything from the experience?

~ ~ ~

Regarding All Quiet On The Western Front

Vladimir Putin also motivated me to read All Quiet On The Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (1929), which I recently finished. I intended to read it when I was writing Medicine For The Blues, but I wanted to stick with American and English sources. (Good-bye To All That by Robert Graves, 1929, is terrific).

Now I am recovering from the shell shock of All Quiet. The book is so well written the effect is devastating. (The 1930 movie is also terrific.) The language of the English translation is wonderfully poetic and elliptical as well as precise and realistic. This is a powerful novel that describes the horrors of war and their effects on the soldiers fighting on the ground.

As it turns out the English translation of All Quiet presents a number of thorny problems. Indeed the 1967 Fawcett Premier (paperback) edition which I read does not even attribute a translator, but it is based on Arthur Wesley Wheen’s English translation of 1929. This article on the web (link below) gets down in the weeds regarding the history of English translations and publications: “Try Simply to Tell,” Translation, Censorship, and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, by Sarah Eilefson.

https://scholarlyediting.org/2017/essays/essay.eilefson.html

Eilefson writes:

‘However, the English-language novel venerated today is in many ways remote from the original German-language text as well as the translation that early readers would have encountered. Moreover, the new and used texts currently on the market differ dramatically from one another, with variants ranging from punctuation to diction to the excision of lines, paragraphs, and whole pages of text. Troublingly, these variants are invisible to most readers. Two primary forces have left their mark on the text available to English speakers today: its translation into English and its censorship in the United States.’ ….

‘The publishing company’s president, Herbert F. Jenkins, said the changes affected “some of the words and sentences” which were “too robust for our American edition.” ’ ….

‘Indeed, according to Brian Murdoch, who prepared a second translation into English, Wheen was fairly loose in his practice, prioritizing the sense of the words over their literal translation. Murdoch wrote, “The first translation of Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front…is marked not by any inaccuracy in the sense (in which respect it is excellent), but precisely by a failure to imitate the style of the narrator, or (worse) the carefully differentiated speech-forms of his fellow-soldiers. Wheen tended to impose his own elevated literary style even on the demotic of North German peat-diggers.” ’

~ ~ ~

After reading these two novels, it is difficult to understand why anyone would go to war, let alone start one.

—Jeff Stookey, May 2022

***

Recent Comments