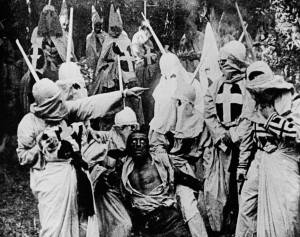

The New York Times, August 2, 2018, still from DW Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, Smith Collection/Gado, via Getty Images

Spike Lee’s new film BlacKkKlansman, based on the true-life account of Ron Stallworth’s experience as the first African-American cop in Colorado Springs in the 1970s, is getting a lot of press these days because it highlights similarities between today’s political realities and those of an earlier time. One of the main reasons I decided to begin publishing my trilogy Medicine for the Blues in 2017 was because of similarities between the politics of the 2016 election and those of the 1920s—that is to say, extreme hatred of those who are not straight white Anglo-Saxon Protestants.

The rise of the Klan in the 1920s followed the release of DW Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, and I reference that film in Acquaintance, book 1, when young Dr. Carl Holman tells his senior colleague that the little he knows about the Klan comes from that movie. Spike Lee uses several clips from Griffith’s film in BlacKkKlansman. Indeed, according to Tim Adams’ interview with Spike Lee in The Guardian, “[Lee’s] response to watching [The Birth of A Nation in film school] was a student film–his first–called The Answer, in which a young black director is hired by a Hollywood studio to remake The Birth of a Nation from his own viewpoint.” BlacKkKlansman follows that early thread in Lee’s career. Later in Adam’s interview, Lee says, “What we wanted to do…was not a history lesson…We wanted the audience to connect with the world they live in today. We thought that the story could make light bulbs go off in their heads.”

Although I am interested in teaching our history, I also want light bulbs to go off in the heads of my readers when they see the power and influence of the Klan in my story set in 1923-24 and compare it to what is happening today. The intolerance expressed by the Klan never really went away; it just went underground. Incidentally, DW Griffith’s next film after The Birth of a Nation was the epic Intolerance, a response to critics of the racism in his earlier film.

The common issue in the lives of LGBT people and people of color is prejudice. Charlene Carruthers, author of Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements, makes this point clearly: “I think black people are inherently queer, frankly. I think black folk are queer in the sense that we’re different.…And then you have queer as like a sexual identity.” (See the Democracy Now! interview, link below.) I have incorporated the theme of racial prejudice in my trilogy not only because the 1920s was an era of Negro jazz and intense racial, ethnic, and religious bias, but because as Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

I hear that there comes a time in the lives of people of color when some parents sit down and explain the dynamics of being colored in a white dominant culture. However, gay children generally do not have the benefit of a similar explanation about being gay in a hetero-dominant culture. Few have the supportive parents who could give this sort of counsel, so LGBT kids have to figure all this out by and for themselves. This reality arises partly out of the fact that most colored people cannot “pass”—there is no way to hide dark skin pigmentation. And most colored parents want their children to grow up knowing that there is nothing wrong with dark skin. Yet many queer people can “pass” as straight if they are able to hide their secret desires and adopt gender normative behavior and mannerisms. This is one of many differences between the bias around skin color versus the bias around sexuality.

Homophobia necessarily figures in my gay love story, but it is not surprising that some intriguing gay themes surface in BlacKkKlansman. A New Yorker review notes that the Klan members “use the N-word casually along with the rest of their crude invective against blacks, Jews, and gays, and in favor of a regime of white supremacy. (Throughout, Lee emphasizes that anti-Semitism as well as homophobia and misogyny are integral to the ideology of white supremacy.)” An ironic turnaround happens when one of the Klansmen suspects Flip, the undercover white stand-in for Ron Stallworth, of being Jewish and demands to see his penis for evidence of circumcision. In response, Flip accuses the Klansman of being gay.

The New Yorker review also comments on a scene in BlacKkKlansman that depicts a speech by Kwame Ture, born Stokely Carmichael, a longtime activist and former Black Panther leader saying, “Ture discusses his childhood delight in the series of Tarzan movies—emphasizing the self-hatred that they imbued him with and likening the experience to Jewish children watching a movie about a concentration camp that stokes them to root for the Nazis. He also links this self-hatred to black Americans’ endurance of life in ‘captive communities’ and violence by racist police officers…” The same reference to self-hatred could be raised for LGBT people who grew up seeing movies that failed to depict people like them or else portrayed them in negative ways. (See Epstein & Friedman’s 1995 film The Celluloid Closet, based on Vito Russo’s book, where, responding to the subject of not being represented in movies, Whoopi Goldberg exclaims, “Tell me about it.”)

It is worth pointing out a parallel between BlacKkKlansman and the Boots Riley film Sorry to Bother You. In both movies, a black protagonist is forced to use his “white voice” to get along in a white world and thus eventually gets himself in trouble. Similarly, many gay boys are forced to use their “straight voice,” to the extent possible, in order to avoid detection and trouble in a straight world. (See David Thorpe’s 2014 documentary Do I Sound Gay?)

When I first started writing these novels, I didn’t know anything about the Klan in early Oregon, but I did learn about the 1988 murder of Mulugeta Seraw, a 27-year-old Ethiopian student who was bludgeoned to death in Portland, OR, by three “skinheads” who said they were followers of the White Aryan Resistance (WAR). In 1990 the leader of WAR, Thomas Metzger, was slapped with $12 million in damages to go to Seraw’s family as a message to other hate groups. Later when I learned about the 1920s Oregon Klan, I knew I had to write about it. I even tried to tie my 1923 love story to the 1980s skinheads with a frame story, not unlike what Spike Lee does in BlacKkKlansman. In the end I was convinced to take that frame story out.

Postscript

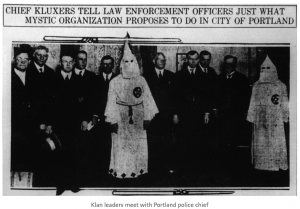

An odd parallel between BlacKkKlansman and the 1920s occurs as Stallworth is assigned to protect KKK Grand Wizard David Duke when he visits Colorado Springs. Stallworth uses the occasion to trick Duke into having his picture taken with him, a black policeman, and just as the picture is being snapped, Stallworth puts his arm around the Klan leader as if they were close friends. There is a famous photo from the 1920s of Portland Klan leaders in full regalia taken with prominent city and law enforcement officials. In his history Sex, Vice, and Misdeeds in Mayor Baker’s Reign, JD Chandler explains that the picture was a setup by Klan leaders, who appeared at the last moment in their robes and hoods alongside the city leaders just before the shutter was clicked. “The headline over the photo read, ‘Chief Kluxers Tell Law Enforcement Officers Just What Mystic Organization Proposes to Do in City of Portland.’ It was a brilliant move for the fledgling KKK, implying that it already had power and influence over the city’s leaders.”

As a side note, The Guardian article mentions that, “In Stallworth’s memoir, the undercover cops foil a planned nail-bomb attack on a gay bar”—a detail that is not included in Lee’s movie.

***

References:

Spike Lee’s film BlacKkKlansman

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7349662/

Black Klansman: Race, Hate, and the Undercover Investigation of a Lifetime by Ron Stallworth

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/37901607-black-klansman

DW Griffith’s The Birth of A Nation, 1915

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birth_of_a_Nation

Tim Adams’ interview with Spike Lee from The Guardian, 29 July 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/jul/29/spike-lee-interview-blackkklansmen-film

Charlene Carruthers interviewed on Democracy Now!

https://www.democracynow.org/2018/9/5/unapologetic_charlene_carruthers_on_her_black_queer

New Yorker review

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-front-row/blackkklansman-reviewed-spike-lees-vision-of-resistance-to-white-supremacy

Epstein & Friedman’s 1995 film The Celluloid Closet based on Vito Russo’s book

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0112651/

David Thorpe’s 2014 documentary Do I Sound Gay?

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3997238/?ref_=nv_sr_1

New York Times, “Sending a $12.5 Million Message to a Hate Group”

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/26/news/sending-a-12.5-million-message-to-a-hate-group.html

Sex, Vice, and Misdeeds in Mayor Baker’s Reign by JD Chandler

https://www.amazon.com/Murder-Scandal-Prohibition-Portland-Misdeeds/dp/1467119539

***

Recent Comments